Born December 13th, 1936 to Princess Tajuddawlah in Geneva, Switzerland, Prince Shah Karim Al Hussaini is the fourth Aga Khan and 49th Ismaili Imam. Known variously as Hazar Imam or Mawla to his followers, he is a British citizen, raised in Kenya, educated at Harvard, who owns property in Italy and has his primary residence in Aiglemont, France. Building on the work of his grandfather, Sir Sultan Muhammed Shah, he has transformed the office of the Imam into the role of an international dignitary.

Viewing entries in

History

Ansary opens his book with a winning account of the earliest days of Islam, from Mohammad's conversion to the wrangling and tussle for leadership which precipitated the Sunni-Shia split.

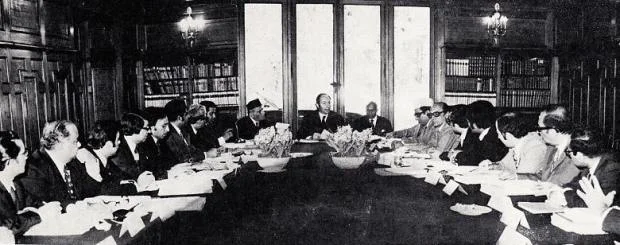

In 1975 Ismailis from across the world gathered to make some monumental decisions and changes to the way they understood and practiced their faith.

Minutes from this historic meeting detail resolutions on the following topics:

Clash of Civilisations?

Prince Karim Aga Khan IV has, on a number of occasions, refuted Samuel P. Huntingdon's theory of a clash of civilisations, saying:

"I disagree with this assessment. In my view it is a clash of ignorance which is to blame"

Sultan Muhammad Shah al-Husayni, Aga Khan III, born in Karachi in November 1877 was 8 years old when he became Imam and was perhaps the most charismatic of the modern era.

The first 'modern' Imam rocketed Ismailis onto the world scene, largely through his extravagant lifestyle and high profile positions.

500 years of doubt and concealment were brought to an end in the mid-18th century as the 43rd Imam of the Ismaili faith came out of hiding in south eastern Iran.

But it's with the 46th Imam, Hasan 'Ali Shah, that Ismaili history took a turn.

Alamut had fallen, the Imam had been slain by his Mongol captors and the Ismaili empire lay in tatters. Ismailis were massacred and dispersed across the region.

The history of the next 500 years is obscure, as Ismaili scholars themselves admit. For the first 200 years the Imams were unknown and even now our Ismaili friend can only claim to know their names.

Muhammad II now ruled as Imam over all Nizari Ismailis from his castle in Alamut, Persia whilst the Syrian Ismaili faction operated under the delegated leadership of the legendary Old Man of the Mountain. Feared by Crusaders and Saladin alike for his devoted assassins who wreaked havoc and terror in the Holy Land, he even had the King of Jerusalem assassinated in 1192.

In 1210, Muhammad II died and was succeeded by his son, Hassan III who immediately ordered his followers to embrace Sunni Islam.

Hasan-i Sabbah was an exceptional and charismatic leader. Under him and his appointed successor the Nizari-Ismaili mini-state, headquartered in Alamut, enjoyed relative success, making raids as far as Jerusalem and the Caucuses and even encroaching on Templar territory.

However, the military successes soon began to dwindle and, with the Imam still hidden somewhere, the Nizari Ismailis (who by the mid-12th century numbered about 60 000), became increasingly disillusioned.

Over a few decades, the Fatimid Ismaili empire succombed to bitter infighting, intense factionalism, leadership crises and defeat at the hands of the Crusaders in the Middle East. Finally, in 1171 Cairo itself was conquered by Saladin and his Sunni warriors. The Ismaili empire was at an end.

Meanwhile, in the mountains of Iran, a shift was taking in place in the identity of Ismailism.

The power-politics and intrigue that marked the early development of Ismailism continued throughout the Fatimid era. In February 1021, the supreme religious and political leader of the Fatimid Empire went for a walk in the hills. Several days later all that was found of him was a bloodied shirt torn by dagger blades. He was succeeded by his infant son. His guardian and second-in-command of the Empire, the vizier, took effective rule.

From then on real power and leadership in the Fatimid empire passed not through the successive imams but from vizier to vizier.

In the early 9th Century many Muslim factions believed in the idea of a 'Mahdi', typically the last leader of their faction, who had been taken away by God but would at some point return as a type of Messiah. This disappearance was known as 'Occultation'. Several prominent Ismaili figures taught that this had happened to Muhammad ibn Ismail, the son of the Imam whose succession had been debated.

However, at the turn of the 10th Century a Syrian named Al-Mahdi announced that Muhammad ibn Ismail and his descendants had in fact been hiding to protect themselves

With the right imagination the history of our Ismaili friend reads like a train-station-filler thriller. The plot is laced with intrigue, secrecy, conniving, murder and power-games; the heroes and villains are kings and sheikhs; the settings are castles, deserts, mosques and souks. And so it is with the first significant turning point.

Our Ismaili friend's history begins in the 7th Century with Muhammad, a middle-aged merchant-cum-philosopher who received in a cave several visions from, he believed, the angel Gabriel. Our Ismaili friend, however, is a Shi'a Muslim (10-20% of Muslims worldwide). As such, he is more interested in Ali, nephew and brother-in-law to Muhammad.